mat200

IPCT Contributor

- Jan 17, 2017

- 16,575

- 27,864

Especially interesting is the story of Robert F Williams ...

Black NRA chapter: “Black Armed Guard” was nothing more than a fancy name for an officially chartered National Rifle Association chapter.

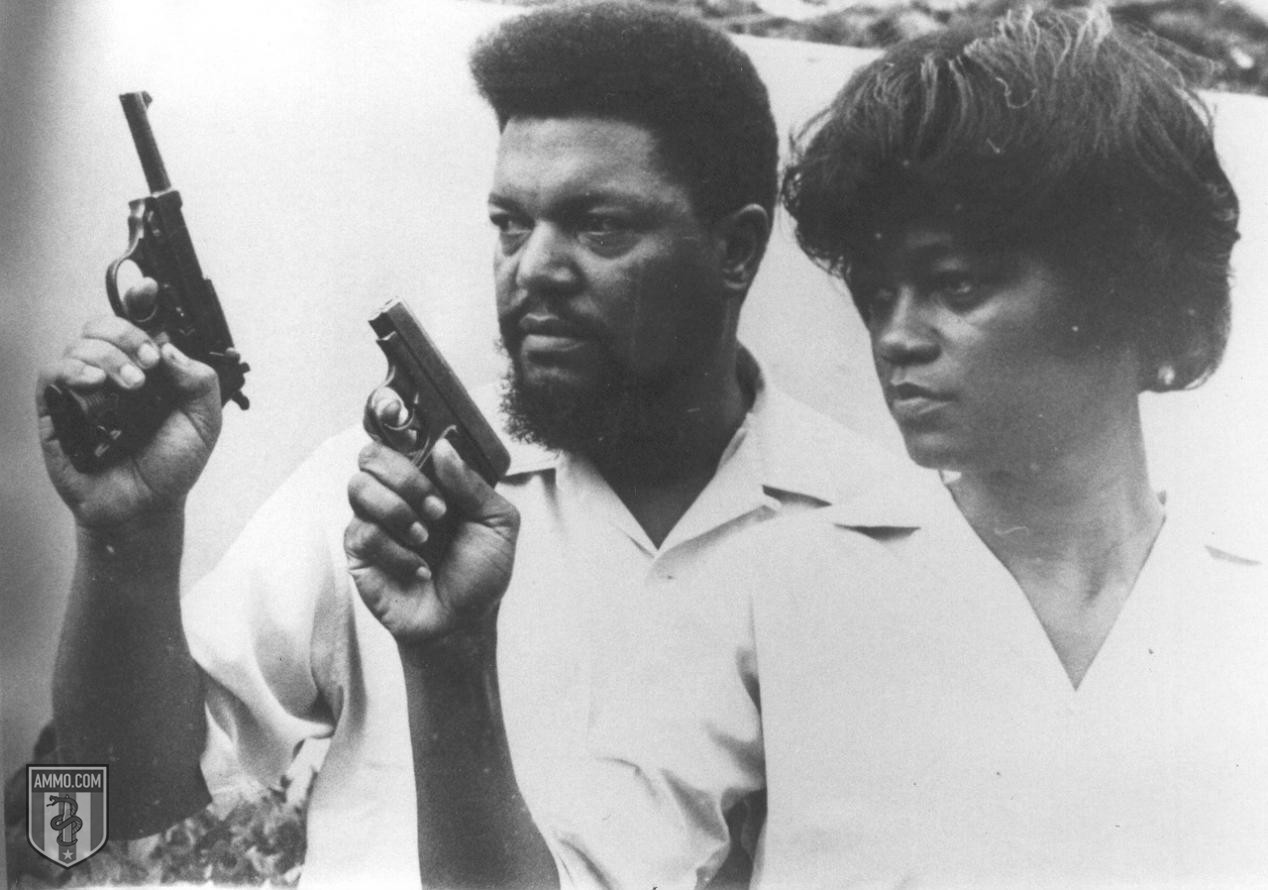

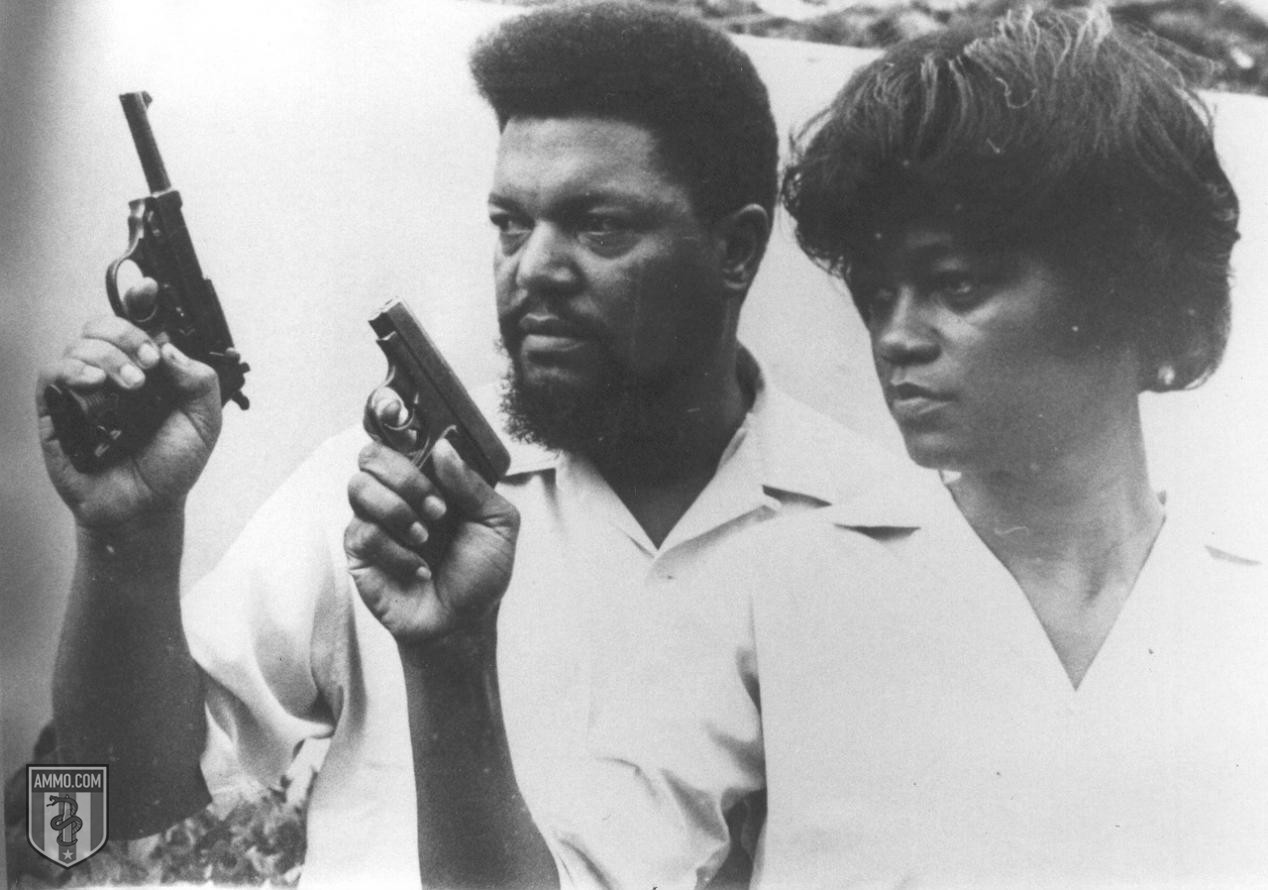

Robert F. Williams and Armed Black Self-Defense

Few are aware that weapons played a pivotal part in the American Civil Rights Movement, specifically through Robert F. Williams. A curious figure in American history, Libertarians are quick to lionize him and his radical approach to black self-defense, but they’ll quickly cool when they learn of his longstanding association with leftist totalitarian politics and governments. Conservatives likewise might initially find themselves infatuated with a man who did not wait for “big government” to deliver his people, but rather leveraged the Second Amendment. Liberals, for their part, might find something to admire in Williams’ notion of liberation, but will recoil in horror when learning that his preferred vehicles for change were the NAACP (great!) and the NRA (terrible!).

Williams was many things, but chief among them was a harbinger of things that would come long after he had fled the United States for what he considered greener pastures in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. He stands across the divide, separating the non-violent, electoral, protest-oriented phase of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s from the later, more militant and direct-action-oriented phase that would arise in the mid-to-late 1960s as the movement became more frustrated (particularly after the assassination of Martin Luther King).

Born in North Carolina in 1925, Williams’ experience mirrors that of many African-Americans of his generation. He moved to Detroit as part of the Second Great Migration, where he was privy to race rioting over jobs. He served in the then-segregated United States Marine Corps for a year and a half after being drafted in 1944. Upon returning to his North Carolina hometown, Williams found a moribund chapter of the NAACP. With only six members and little opposition, he used his USMC training to commandeer the local branch and turn it in a decidedly more military direction. The local chapter soon had over 200 members under Williams’ leadership. If nothing else, his leadership was effective at building the movement from the ground up.

An early incident is particularly instructive in how effective these new tactics were. The KKK was very active in Monroe, with an estimated 7,500 members in a town of 12,000. After hearing rumors that the Klan intended to attack NAACP chapter Vice President Dr. Albert Perry’s house, Williams and members of the Black Armed Guard surrounded the doctor’s house with sandbags and showed up with rifles. Klansman fired on the house from a moving vehicle and the Guard returned fire. Soon after, the Klan required a special permit from the city’s police chief to meet. One incident of self-defense did more to move the goalposts than all previous legislative pressure had.

Monroe’s Black Armed Guard wasn’t a subsidiary of the Communist Party, nor an independent organization like the Black Panther Party that would use similar tactics of arming their members later. In fact, “Black Armed Guard” was nothing more than a fancy name for an officially chartered National Rifle Association chapter.

His 1962 book, Negroes With Guns, was prophetic for the Black Power movement to come later on in the decade. But Williams is noteworthy for his lack of revolutionary fervor, at least early on. Williams was cautious to always maintain that the Black Armed Guard was not an insurrectionary organization, but one dedicated to providing defense to a group of people who were under attack and lacking in normal legal remedies:

"To us there was no Constitution, no such thing as 'moral persuasion' – the only thing left was the bullet...I advocated violent self-defense because I don't really think you can have a defense against violent racists and against terrorists unless you are prepared to meet violence with violence, and my policy was to meet violence with violence."

Robert Williams

Williams himself is an odd figure, not easily boxed into conventional political labels. While often lauded, for example in a PBS Independent Lens hagiography, it’s worth noting that Williams spent a number of years operating Radio Free Dixie, a radio station broadcast from Communist Cuba that regularly denounced the American government. He urged black soldiers to revolt during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Williams personally praised the Watts riots in 1966, simultaneously invoking “the spirit of ‘76.” Radio Free Dixie ceased operations in 1965, when Williams relocated to Red China at the personal request of Chairman Mao Zedong (hardly a proponent of freedom). Williams happily accepted, and this is where he remained for the rest of his exile from the United States – avoiding dubious charges of kidnapping white activists, Williams claimed he was defending from Klan attacks.

However, it’s not entirely fair to brand Williams a pliant, party-line Communist, either. Even while hobnobbing with the elite of the Chinese Communist Party, Williams regularly denounced the U.S. Communist Party as “Gus Hall’s idiots.” To some degree, this reflects internal divisions in the international Communist movement at the time, with national parties and internal factions lining up between Moscow and Beijing. But he also refused to rule out any sort of deal between himself and the federal government – or the far right, for that matter – on the grounds that he would do anything to avoid prison. He gave speeches in China denouncing the United States, including one where he associated Robert Kennedy with an alleged system of international white supremacy.

Upon returning to the United States, Williams was put on trial for the alleged kidnapping and was extradited to North Carolina from Michigan. By the time his case went to trial in 1975, it was a cause celebre among the American far left and the charges were soon dropped. His later years were marked by a lack of political activity. He received a grant from the Ford Foundation to work in the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan. He seemed to have little interest in leading the more militant, Black Power incarnation of the Civil Rights Movement that had emerged in his exile. The title of his New York Times obituary is rather telling: “Outspoken and Feared but Largely Forgotten.”

Williams is a confusing figure, one that’s hard to figure out and even harder for people of any political persuasion to take a hard line in favor of. An iconoclast and a malcontent, he was simultaneously capable of self-sacrifice, exiling himself from his homeland, as well as blatant (and almost certainly appropriate) self-interest, ready to cut any kind of a deal to keep himself out of jail. No matter what your opinion is of Robert F. Williams and his role in bringing together blacks and guns, one thing's for sure – we won’t be seeing him on the front of dollar bills any time soon.

ref:

ammo.com

ammo.com

Black NRA chapter: “Black Armed Guard” was nothing more than a fancy name for an officially chartered National Rifle Association chapter.

Robert F. Williams and Armed Black Self-Defense

Few are aware that weapons played a pivotal part in the American Civil Rights Movement, specifically through Robert F. Williams. A curious figure in American history, Libertarians are quick to lionize him and his radical approach to black self-defense, but they’ll quickly cool when they learn of his longstanding association with leftist totalitarian politics and governments. Conservatives likewise might initially find themselves infatuated with a man who did not wait for “big government” to deliver his people, but rather leveraged the Second Amendment. Liberals, for their part, might find something to admire in Williams’ notion of liberation, but will recoil in horror when learning that his preferred vehicles for change were the NAACP (great!) and the NRA (terrible!).

Williams was many things, but chief among them was a harbinger of things that would come long after he had fled the United States for what he considered greener pastures in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. He stands across the divide, separating the non-violent, electoral, protest-oriented phase of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s from the later, more militant and direct-action-oriented phase that would arise in the mid-to-late 1960s as the movement became more frustrated (particularly after the assassination of Martin Luther King).

Born in North Carolina in 1925, Williams’ experience mirrors that of many African-Americans of his generation. He moved to Detroit as part of the Second Great Migration, where he was privy to race rioting over jobs. He served in the then-segregated United States Marine Corps for a year and a half after being drafted in 1944. Upon returning to his North Carolina hometown, Williams found a moribund chapter of the NAACP. With only six members and little opposition, he used his USMC training to commandeer the local branch and turn it in a decidedly more military direction. The local chapter soon had over 200 members under Williams’ leadership. If nothing else, his leadership was effective at building the movement from the ground up.

An early incident is particularly instructive in how effective these new tactics were. The KKK was very active in Monroe, with an estimated 7,500 members in a town of 12,000. After hearing rumors that the Klan intended to attack NAACP chapter Vice President Dr. Albert Perry’s house, Williams and members of the Black Armed Guard surrounded the doctor’s house with sandbags and showed up with rifles. Klansman fired on the house from a moving vehicle and the Guard returned fire. Soon after, the Klan required a special permit from the city’s police chief to meet. One incident of self-defense did more to move the goalposts than all previous legislative pressure had.

Monroe’s Black Armed Guard wasn’t a subsidiary of the Communist Party, nor an independent organization like the Black Panther Party that would use similar tactics of arming their members later. In fact, “Black Armed Guard” was nothing more than a fancy name for an officially chartered National Rifle Association chapter.

His 1962 book, Negroes With Guns, was prophetic for the Black Power movement to come later on in the decade. But Williams is noteworthy for his lack of revolutionary fervor, at least early on. Williams was cautious to always maintain that the Black Armed Guard was not an insurrectionary organization, but one dedicated to providing defense to a group of people who were under attack and lacking in normal legal remedies:

"To us there was no Constitution, no such thing as 'moral persuasion' – the only thing left was the bullet...I advocated violent self-defense because I don't really think you can have a defense against violent racists and against terrorists unless you are prepared to meet violence with violence, and my policy was to meet violence with violence."

Robert Williams

Williams himself is an odd figure, not easily boxed into conventional political labels. While often lauded, for example in a PBS Independent Lens hagiography, it’s worth noting that Williams spent a number of years operating Radio Free Dixie, a radio station broadcast from Communist Cuba that regularly denounced the American government. He urged black soldiers to revolt during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Williams personally praised the Watts riots in 1966, simultaneously invoking “the spirit of ‘76.” Radio Free Dixie ceased operations in 1965, when Williams relocated to Red China at the personal request of Chairman Mao Zedong (hardly a proponent of freedom). Williams happily accepted, and this is where he remained for the rest of his exile from the United States – avoiding dubious charges of kidnapping white activists, Williams claimed he was defending from Klan attacks.

However, it’s not entirely fair to brand Williams a pliant, party-line Communist, either. Even while hobnobbing with the elite of the Chinese Communist Party, Williams regularly denounced the U.S. Communist Party as “Gus Hall’s idiots.” To some degree, this reflects internal divisions in the international Communist movement at the time, with national parties and internal factions lining up between Moscow and Beijing. But he also refused to rule out any sort of deal between himself and the federal government – or the far right, for that matter – on the grounds that he would do anything to avoid prison. He gave speeches in China denouncing the United States, including one where he associated Robert Kennedy with an alleged system of international white supremacy.

Upon returning to the United States, Williams was put on trial for the alleged kidnapping and was extradited to North Carolina from Michigan. By the time his case went to trial in 1975, it was a cause celebre among the American far left and the charges were soon dropped. His later years were marked by a lack of political activity. He received a grant from the Ford Foundation to work in the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan. He seemed to have little interest in leading the more militant, Black Power incarnation of the Civil Rights Movement that had emerged in his exile. The title of his New York Times obituary is rather telling: “Outspoken and Feared but Largely Forgotten.”

Williams is a confusing figure, one that’s hard to figure out and even harder for people of any political persuasion to take a hard line in favor of. An iconoclast and a malcontent, he was simultaneously capable of self-sacrifice, exiling himself from his homeland, as well as blatant (and almost certainly appropriate) self-interest, ready to cut any kind of a deal to keep himself out of jail. No matter what your opinion is of Robert F. Williams and his role in bringing together blacks and guns, one thing's for sure – we won’t be seeing him on the front of dollar bills any time soon.

ref:

The Untold History of Black NRA Gun Clubs + Civil Rights

What do the NRA, Black Panthers, and Ronald Reagan have in common? Read on to learn the role of pro-gun African-Americans in America’s gun control battle.